Charging stations for electric vehicles: the Autorité issues its opinion on the competitive functioning of electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVCI)

Background

At a time when the European Union has set itself the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, the transport sector must evolve to reduce its impact on the environment. Accordingly, the deployment and pricing of electric vehicle charging infrastructure (“EVCI”) and the creation of associated services are key to the decarbonisation of the transport sector. The strategic contract for the automobile sector in France includes a target of 400,000 publicly accessible charging stations by 2030, versus 100,000 in 2023.

To prepare an overview of the competitive landscape in the EVCI sector, the Autorité started inquiries ex officio in February 2023 and then launched a public consultation in May 2023, receiving 81 responses to the questionnaires sent out and six open contributions. The Autorité also drew on the work of the sector-specific regulators concerned, the French energy regulator (Commission de régulation de l’énergie – CRE) and the French transport regulator (Autorité de régulation des transports – ART).

Scope

As part of this opinion, which focuses on mainland France (excluding Corsica), the Autorité has examined two complementary sectors that are essential to the mass deployment of light electric vehicles (excluding heavy goods vehicles and two-wheelers) and their adoption by the French:

- publicly accessible EVCI and related activities (installation and operation of EVCI and provision of mobility and interoperability services);

- EVCI for private use, in apartment buildings.

Recommendations for the French government, sector-specific regulators and industry players

This opinion is addressed to the French State (legislator, shareholder and concession holder), the relevant local and regional authorities, sector-specific regulators and the many players in the value chain that are also responsible for stimulating competition in the two sectors under analysis:

- legislative, regulatory and organisational recommendations are made to supplement the legal framework in which these multiple players operate and to optimise government support for these two growth sectors. The aim is twofold, namely to create the right conditions for the emergence of a competitive sector, and to support consumers as they change their consumption habits;

- at the same time, a number of non-exhaustive potential competitive risks are highlighted, which require particular vigilance to maintain competition on the merits and foster innovation, as well as the quality and diversity of the offering in these emerging sectors.

The Autorité recalls that industry players can now request informal guidance in the area of sustainability, as part of the notice published on 27 May 2024.

The public charging station sector

How the sector works

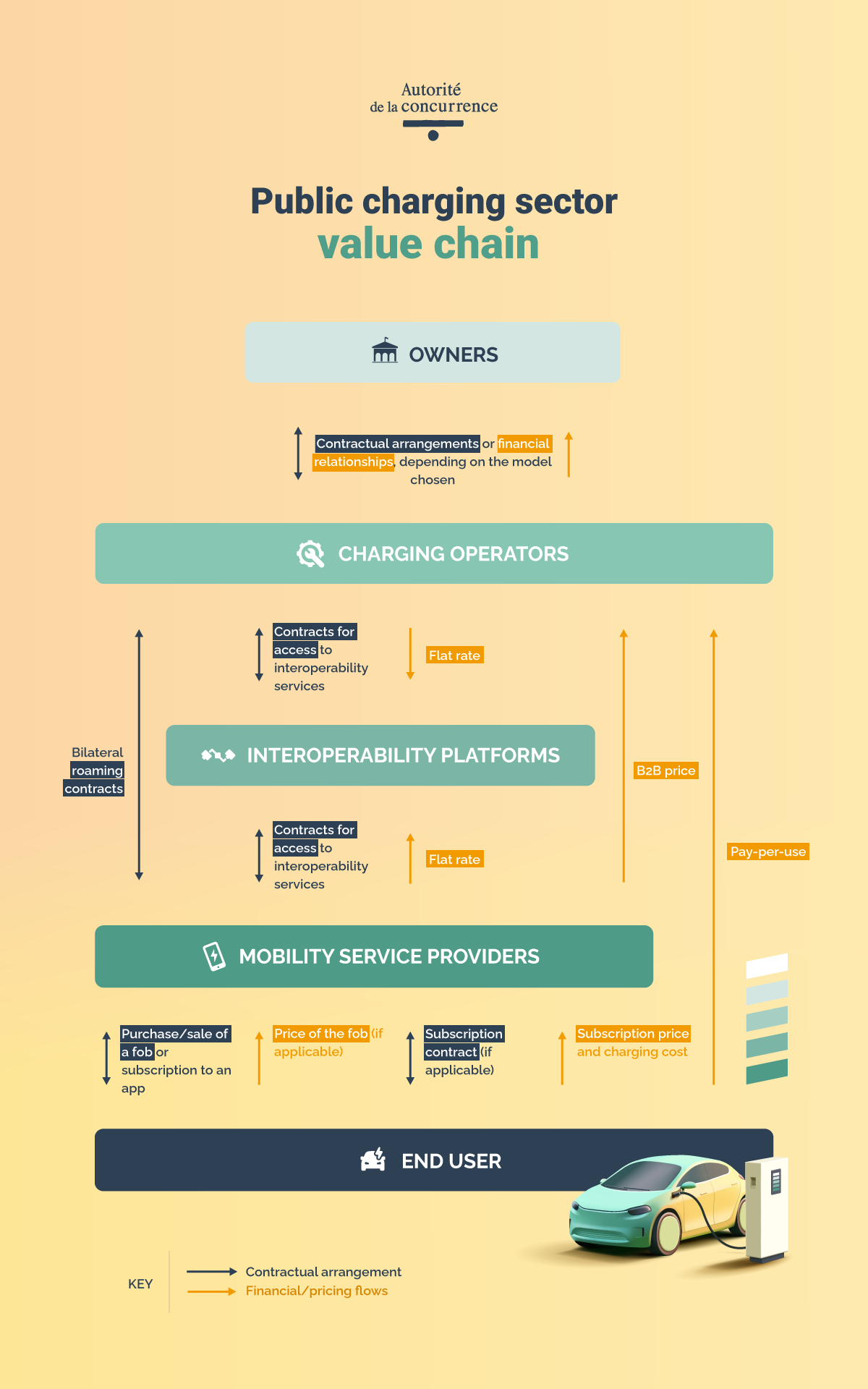

The publicly accessible EVCI sector involves many different players that interact through contractual relationships of various kinds:

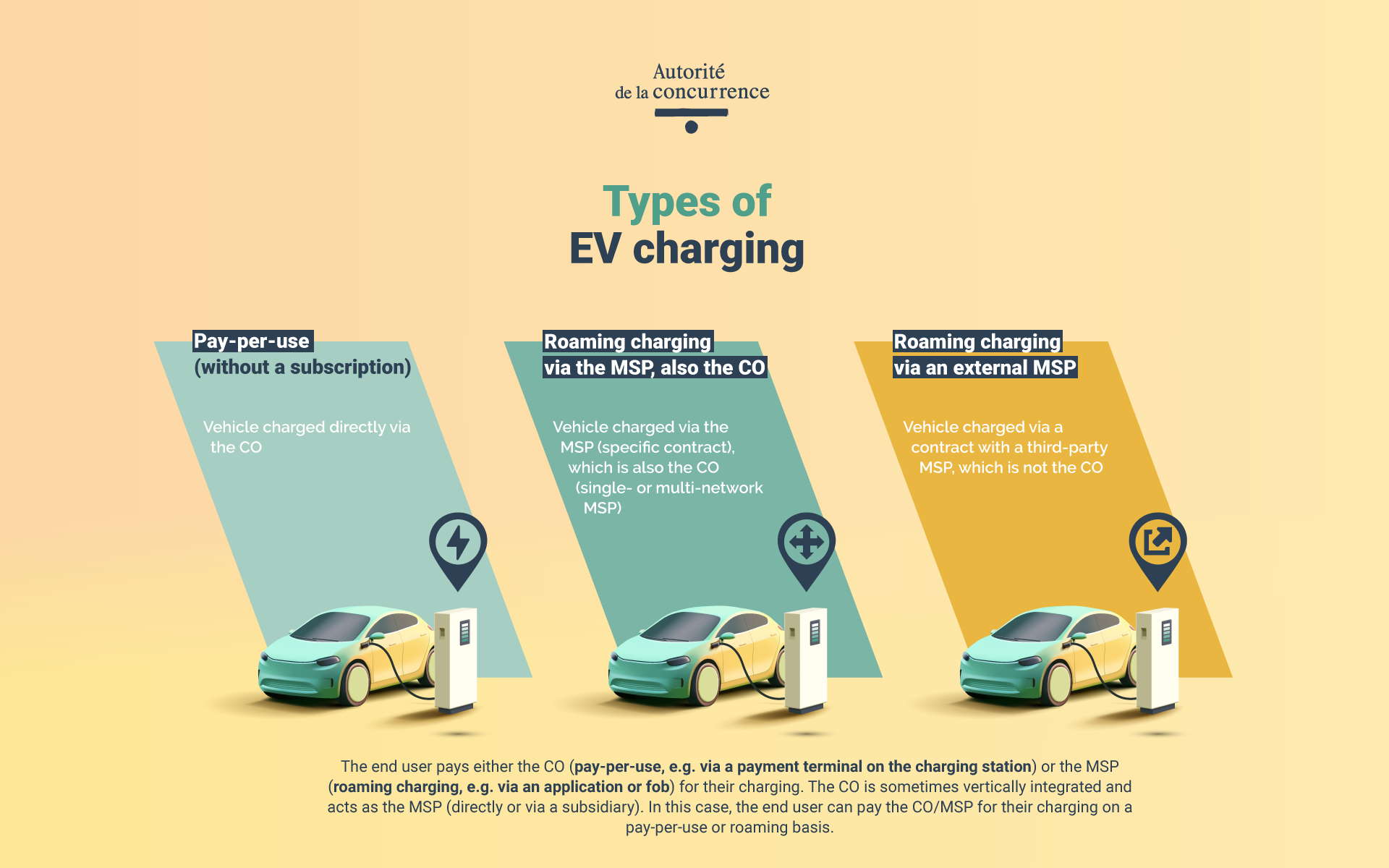

- charging operators (“COs”), which install and operate EVCI. They are selected by site owners either through a competitive bidding process with a call for tender, or without a competitive bidding process by mutual agreement. COs offer end users the option of paying for their charging on a “pay-per-use” basis, i.e. without prior registration or an existing customer relationship (e.g. payment by credit card);

- mobility service providers (“MSPs”), which offer charging services to end users through dedicated applications and fobs, or as part of a subscription;

- interoperability platforms, which link COs and MSPs and facilitate and secure relations between these two categories of players.

Therefore, the end user pays either the CO (pay-per-use) or the MSP (roaming charging) for their charging. In the latter case, the CO sells a charging session to the MSP at a wholesale rate and the MSP then determines the charging price invoiced to the end user. This framework is defined in the roaming agreements concluded between COs and MSPs, either directly or via the services of an interoperability platform.

Charging stations are located at sites managed by a variety of owners: the French State and decentralised government departments, motorway concession operators (“MCOs”), local and regional public authorities and public bodies, and owners of private land accessible to the public (shopping centres, restaurants, etc.).

The levers of action needed to encourage the growth of electromobility

The growth of electromobility is affected by a paradox. The mass adoption of electric vehicles by consumers depends on the existence of a dense network of robust and reliable EVCI, giving users confidence and reducing their worries about the risk of running out of charge. However, installing EVCI requires substantial investment, and the return on this investment depends on the electrification rate of the French car fleet. The development of a dense EVCI network and consumer adoption of electric vehicles are therefore interdependent. Against this backdrop, the Autorité has identified two cross-functional levers for action to ensure the efficient and successful deployment of publicly accessible EVCI.

- In favour of the development of more coherent and balanced EVCI geographical coverage

During its investigation, the Autorité found persistent regional disparities in the deployment of EVCI. Moreover, according to French environmental agency Ademe, “[o]nly 15% of French people consider their region to be sufficiently covered by charging stations”.

These disparities can be explained by the large number of owners involved, which can hinder the emergence of an overall vision. In this context, without more determined and targeted public intervention, densely populated areas are likely to continue to attract COs as a priority, given their profitability, until they are all equipped, potentially for fairly long periods. This will reduce the incentive to install EVCI in sparsely populated areas, a market failure that requires public support.

- The Autorité proposes improving the diagnostic process, in particular by ensuring the comprehensiveness of the public database, notably to enable more accurate identification of areas with a very low density of charging stations and better targeting of public aid.

- The Autorité recommends strengthening the resources of the inter-ministerial coordinator, by creating an inter-ministerial body to ensure coordination between the different owners, and planning and monitoring of deployment at national level, across all charging powers, within the framework of precisely defined missions.

The Autorité invites COs that are considering pooling their investments to equip very low-density areas with EVCI to enter into informal dialogue with the Autorité on the planned agreements, within the framework of the notice of 27 May 2024 on informal guidance in the area of sustainability.

- In favour of greater pricing transparency

The charging experience remains complex for users, and charging pricing particularly opaque.

In particular, the Autorité found that there is a lack of information for consumers concerning the price of charging, both before charging for comparing prices and after charging for quickly identifying the price actually paid.

The different types of charging contribute to this pricing opacity. On a given charging station, a user will pay a different price depending on whether they are charging on a “pay-per-use” or roaming basis. When roaming, the price will also differ from one MSP to another.

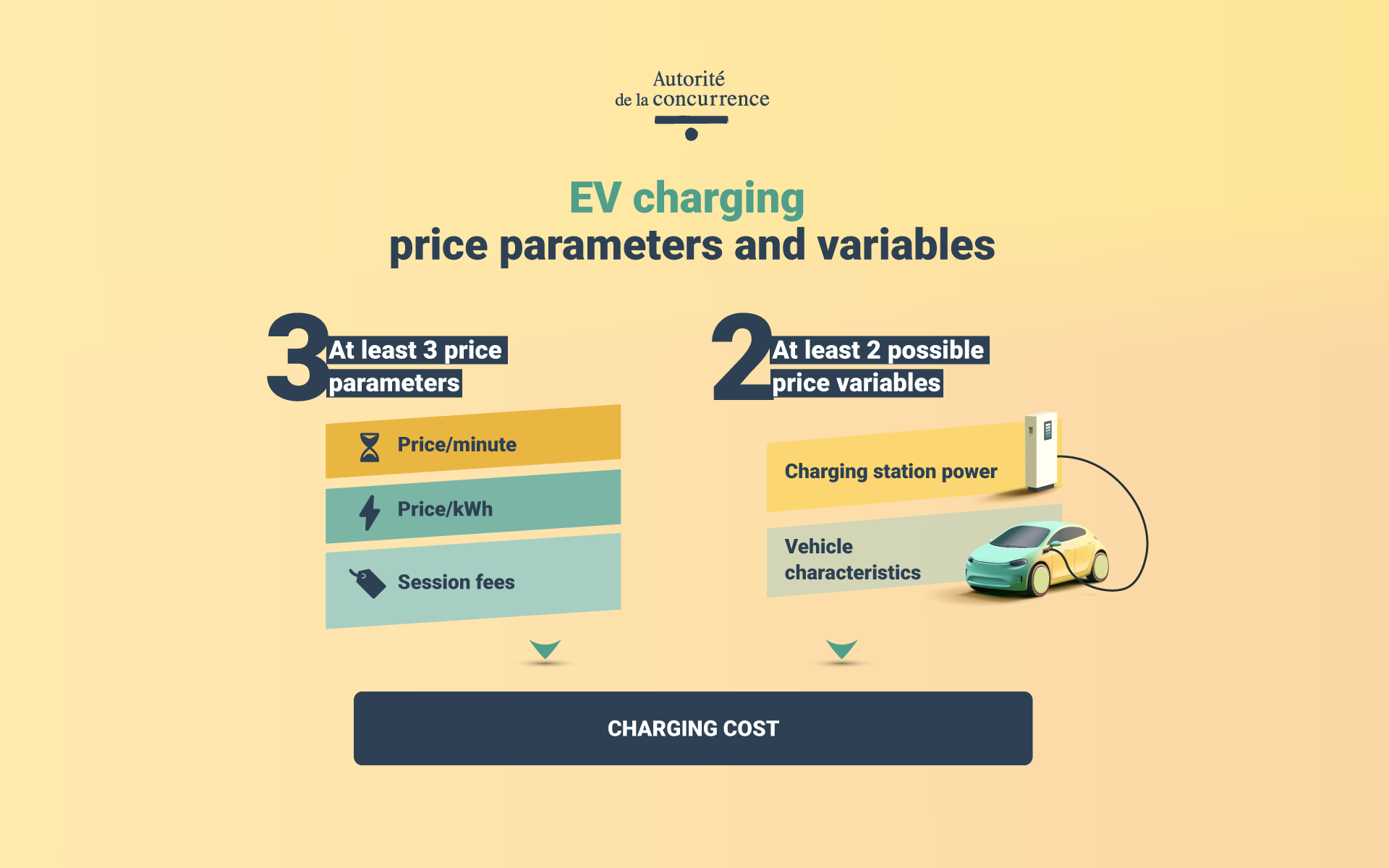

In addition, regardless of the type of charging, the price charged to the end user is likely to depend on a range of parameters and variables.

As a result, pricing structures are very diverse, making it difficult for end users to predict prices. Due to the multiple potential pricing scenarios, users are unable to make informed choices between the different offerings available, especially as there is no guarantee that prices will be displayed.

- The Autorité recommends that COs and MSPs charge for charging on a per kWh basis (to which may be added, for COs, a per-minute charge and, for MSPs, any fees applied). The Autorité also recommends improving the comprehensiveness of the existing public database by requiring both COs and MSPs to transmit and update their kWh prices in real time, by charging station and, where applicable, ancillary fees. A more comprehensive database will facilitate the emergence of price comparators.

- The Autorité considers that MSPs should also be required to present their offerings transparently, distinguishing on their website or any other commercial medium between the price per kWh, per charging station (specifying that the price is likely to change according to the CO price) and any other applicable fees.

- The Autorité suggests experimenting with the installation of signage on motorways, displaying the price of “pay-per-use” charging before charging stations and at the main motorway entrances.

- With regard specifically to post-charging price information, the Autorité recommends that COs and MSPs should be required to display the price paid by the electric vehicle user at the end of each charging session, on the terminal in the case of “pay-per-use” charging and on the MSP app in the case of roaming charging.

While greater price transparency may increase the risk of collusion in the market, the Autorité considers that, in this emerging sector, consumer information takes precedence over such risk, which will in any case be monitored by the Autorité. In addition, increased price transparency reduces search costs for consumers, which ultimately stimulates competition between COs and between MSPs.

The competitive situation in the market for the installation and operation of publicly accessible EVCI (COs)

In France, there are around 410 active COs. Their business models are not yet stabilised. Furthermore, as the installation of EVCI, particularly for fast and ultra-fast charging, requires significant investment with uncertain returns, the sector could see medium-term consolidation. The Autorité will remain vigilant to ensure that any such sector consolidation does not hinder competition.

For the moment, the offer is relatively fragmented, and while barriers to entry and expansion do exist, they have not hindered the emergence of new entrants. While some COs are specialised and can thus be described as “pure players” (Electra, Fastned, etc.), others also operate at different levels of the value chain or in related markets, such as energy companies (EDF, TotalEnergies, Engie, etc.), oil and gas companies (TotalEnergies and Shell) or car manufacturers (Ionity, which is owned by a consortium of car manufacturers, Tesla, etc.). A smaller circle of COs, whose identity varies according to the segment (motorway/non-motorway), seems to be gradually acquiring greater importance.

- The competitive advantages of COs

The first competitive advantage relates to land ownership and preferential access to strategic locations, for example close to motorway exits.

The Autorité has also identified other competitive advantages, such as the vertical or conglomerate integration of activities within a single group, for example the combination of CO/MSP activities. Accordingly, a CO could implement a number of behaviours to promote its own activities. For example, the CO could list its charging stations via its mobility services, in a preferential way compared to the charging stations of competing COs, in terms of both quality (real-time availability, location, etc.) and pricing. Vertically integrated COs could also offer competing MSPs less favourable commercial terms for listing their charging stations versus their own mobility services, or even refuse to list their charging stations.

The other combinations of activities analysed include the following:

- oil and gas companies, which have a competitive advantage linked, for example, to their pre-existing presence in motorway service stations;

- energy suppliers, which can enjoy preferential access to electricity to power charging stations;

- electric vehicle manufacturers, which could, for example, offer preferential charging conditions to drivers of vehicles of the brand(s) concerned.

In this respect, the Autorité reiterates that the potential existence of a leverage effect that could be implemented by certain COs holding market power on upstream, downstream and/or related markets calls for particular vigilance regarding changes in the competitive structure of the market and practices that could be implemented by certain players.

- CO award and selection procedures: room for improvement

On the concession motorway network

On the concession motorway network, the Autorité found that the equipment targets set by the French government for service stations (with additional services such as catering or fuel distribution) have been achieved, and that certain rest areas are also beginning to benefit from the installation of equipment.

However, the Autorité considers that competition could be further stimulated. While dedicated EVCI sites can be allocated through competitive bidding processes, MCOs can also choose to amend current sub-concession contracts, with a possible third-party operator agreement between the sub-concessionaire and a CO.

- The Autorité recommends that MCOs restrict the use of mutual agreement processes for the allocation of their sites to exceptional and justified cases. The Autorité also recommends making the signature of amendments conditional on prior approval from the ART.

- Where recourse to an amendment/third-party operator agreement is justified, the Autorité invites MCOs to ensure identical contractual requirements to those in the CO selection criteria (service quality, technical and environmental quality, price moderation, etc.) provided for under the standard procedure.

- The Autorité also recommends the introduction of CO monitoring and control procedures, similar to those used in sub-concession contracts.

In addition, the Autorité noted that when selection is made by a competitive bidding process, the structuring and criteria used are likely to have an impact on market competition. When the various activities at service stations – the operation of the EVCI, the distribution of traditional fuels and the management of a restaurant, shop or any other service – are not divided into separate lots, diversified COs like oil and gas companies have an advantage. Similarly, the number of stations included in calls for tenders for EVCI may prevent some COs from bidding.

- The Autorité recommends that MCOs launch separate calls for tender for each type of activity in a given station or stations and, in any case, specific calls for tender for EVCI.

- The Autorité also recommends that MCOs select the most commonly used approach to date, which involves limiting the number of stations per call for tender for future consultations and when they are renewed.

As regards CO selection criteria, while they are governed by the French Highway Code, the Autorité agrees with the analysis of the ART, according to which the criterion relating to the fees paid to MCOs should not be given priority over price moderation, a criterion whose implementation could be improved, on the basis of the recommendations of the ART. Furthermore, given the key role of the ART in the development of healthy competition between motorway COs, the Autorité recommends strengthening its powers.

- The Autorité invites the French government to implement the recommendations of the ART on price moderation, such as the introduction of a price index for electric charging similar to that published by the Directorate General for Energy and Climate (“DGEC”) for traditional fuels.

- The Autorité also calls on the legislator to provide for the ART to give assent, rather than a simple opinion, for the validation of procedures for awarding contracts for EVCI on the motorway network.

The Autorité also draws attention to the fact that contact durations can freeze the competitive situation. Regardless of the duration, contracts must also contain a clause providing for the upgrading of EVCI equipment during the contract term (by the existing CO and/or by a second CO selected after a new competitive bidding process), with provision for financial compensation if the investment is not recouped over the remaining contract term.

- The Autorité therefore invites MCOs to ensure that contract terms are determined according to the nature and amount of the investments.

- The Autorité also recommends that the clause providing for the upgrading of EVCI equipment during the contract term be accompanied by details of how the CO will be financially compensated if the investment in the EVCI is not recouped during the remaining contract term.

- The Autorité suggests that MCOs retain sufficient contractual flexibility to select a second CO in a given station.

On the non-concession road network

The non-concession road network, managed by decentralised government departments, includes toll-free motorways and national roads. On the non-concession road network, the French State has not set any targets for the installation of EVCI, unlike the obligation imposed on MCOs to install EVCI in service stations on the concession motorway network by 1 January 2023. As a result, the installation of EVCI in service stations on the non-concession network remains piecemeal.

Although the award procedures are the same as for the concession motorway network, the obstacles to competition are more pronounced. Amendments for the deployment of EVCI is the rule, and advertising and competitive bidding processes the exception.

In addition to all the recommendations applicable to the concession network, the Autorité suggests, in particular, that the French Inter-Departmental Highways Authority (DIR) be given a target for the EVCI penetration rate, and that its achievement be made public.

On the public land of local and regional public authorities

Local and regional public authorities play an important role in the deployment of EVCI, particularly for people who do not have a charging station at home. According to UFC-Que Choisir, in 2021 60% of publicly accessible charging stations were financed by local and regional public authorities or public bodies. The Autorité was able to analyse several management choices made by local and regional authorities. While some authorities have chosen to manage EVCI themselves, others have decided to entrust EVCI management to one or more COs. The Autorité considers that local and regional public authorities should ensure that competition is fostered at local level, in order to encourage the presence of several COs. Accordingly, the Autorité calls on local and regional public authorities to systematically study the competitive impacts associated with the choice of management, and makes a number of general recommendations.

- The Autorité recommends limiting the inclusion of exclusivity clauses in favour of COs concerning the management of the charging service.

- As far as possible, the Autorité recommends that several lots comprising a certain number of charging stations be organised, with the ultimate selection of several COs whose stations will compete within the zone. Lots should be constructed in such a way as to combine attractive and less attractive areas.

- The Autorité invites the competent local and regional public authorities to set contract terms that are correlated to the nature and amount of the COs’ investments.

- As far as possible, there should be a system for monitoring COs, particularly with regard to prices and service quality (availability rate, turnaround time for maintenance and repair, etc.), and penalties imposed in the event of non-compliance.

In addition, the Autorité noted that local and regional public authorities can establish ECVI development masterplans (“EVCIMs”) for the deployment of EVCI, whereby “local and regional authorities’ priorities for action for achieving sufficient charging facilities for plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles for local and transit traffic can be defined”.

There are four phases involved in implementing an EVCIM, including a diagnostic phase which could be improved.

- The Autorité recommends making EVCIMs mandatory and involving the DIR in their preparation, and applying an administrative penalty in the event of non-compliance with Articles L. 353-6 and D. 353-6 of the French Energy Code (Code de l’énergie) (obligation for COs to transmit information for the preparation of an EVCIM).

- The Autorité invites local and regional public authorities to include a specific assessment of needs in terms of geographical coverage, including private terminals, in the diagnosis required to prepare an EVCIM, in order to provide an appropriate response to needs that vary from one area to another.

On private property

Publicly accessible EVCI on private property (food and specialist retailers, shopping centres, hotels, fast-food chains, etc.) is growing rapidly, under the combined effect of the law imposing equipment and pre-equipment obligations and the increasing importance of destination charging, i.e. charging at the destination of the electric vehicle user. The presence of charging stations in car parks can therefore influence consumers’ decisions in favour of a particular banner and thereby constitute a parameter of competitive. In this context, the Autorité found relatively long-term partnerships between private players, sometimes with exclusivity clauses in favour of COs.

The Autorité draws operators’ attention to the risks associated with the characteristics of certain contracts concluded on a national scale, which are likely to freeze the competitive situation, a fortiori on particularly attractive sites, for a long period.

The competitive situation for mobility services (MSPs) and interoperability services (interoperability platforms)

- The market for the supply/subscription of mobility services

In France, there are around 90 active COs. However, the Autorité found contrasting competitive dynamics. In the same way as for COs, specialised MSPs are growing (e.g. ChargeMap, Plugsurfing) alongside MSPs that are also active at a different level of the value chain or in related markets. While this vertical and/or conglomerate integration can generate competitive advantages, it can also lead to competitive risks.

Furthermore, the Autorité found that the development of “per-per-use” charging and Plug & Charge (a technology whereby the vehicle communicates directly with the charging station to charge, by plugging in) could weaken or even, in the long term, lead to the disappearance of certain MSPs.

In any case, the implementation of Plug & Charge is likely to lead to a situation in which an electric vehicle is equipped by only one MSP, enabling the vehicle to be charged only via the services of the MSP in question. Consumer choice would then be restricted, which could significantly disrupt competitive dynamics.

The Autorité recommends that consumers be able to freely choose the MSP when the Plug & Charge functionality is compatible with the electric vehicle.

- The market for the provision/subscription of interoperability services

The Autorité found that the market for the provision of interoperability services is concentrated around two main players, Gireve and Hubject. Gireve, the most widely used platform in France, has long enjoyed a special status as the only platform able to issue COs with interoperability certificates, which are essential for receiving subsidies under the Advenir programme. The Autorité stresses the constant need to ensure a level playing field between interoperability platforms.

The Autorité recommends that all interoperability platforms operating in France be allowed to issue the interoperability certificates required by COs to access public subsidies.

In addition, the Autorité analysed the issues surrounding the technical protocols developed by interoperability platforms, in particular to support the development of Plug & Charge.

The Autorité recommends establishing a secure and transparent framework for recognising the authenticity of the certificates needed to develop Plug & Charge.

- Interactions between players at different levels of the value chain

Relationship between COs and MSPs

The bargaining relationship between COs and MSPs seems generally favourable to COs. In its opinion, the Autorité points out, in particular, the risk of MSPs being excluded, which could result from the pricing policy applied by certain COs to MSPs. Some COs invoice MSPs for a “B2B” charging session at the public price (excluding VAT) of the “B2C” one-off charge offered by COs, which ultimately prevents MSPs from offering end users competitive pricing.

The European Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (“AFIR”), adopted in September 2023, represents an initial response to the problem, providing a framework for the pricing policy of COs vis-à-vis MSPs. The price differentiation applied by COs must therefore be proportionate and objectively justified.

If necessary, competition law can provide a second form of response. The Autorité reserves the right to intervene on the basis of provisions prohibiting anticompetitive practices, and to sanction any pricing or non-pricing strategy that constitutes either an abuse of dominant position or a cartel. The Autorité will also be attentive to the existence of clauses likely to restrict the ability of the buyer, in this case the MSP, to determine its selling price.

In any event, the Autorité invites the contracting parties to carry out an audit of their roaming agreements, in the light not only of competition law, but also of the law on restrictive competitive practices and contract law.

Interactions between interoperability platforms and COs and MSPs

The vertical partnerships forged between MSPs and COs via interoperability platforms are likely to play a pro-competitive role, by helping to decompartmentalise the EVCI network and offering users the possibility of charging at a wide range of charging stations. In this respect, the Autorité found during its investigation that contracting with interoperability platforms remains essential, particularly for new entrants, whether COs or MSPs, and offers many advantages.

Nevertheless, the Autorité warns of certain competitive risks associated with the contracts concluded, and makes a number of recommendations.

- The Autorité recommends that the legislator/government ensure that the prices of the interoperability services offered by platforms are reasonable, transparent and non-discriminatory.

- The Autorité calls on the platforms to preserve the non-exclusive nature of their contracts, as well as the possibility for operators to renegotiate and terminate them, free of charge.

The proactive approach of professional associations and organisations

The Autorité found that the proactivity of professional associations and organisations in the publicly accessible EVCI sector inevitably causes a number of competitive risks (conditions of membership of professional associations and organisations, exchanges of sensitive information that potentially restricts competition, pricing guidelines, etc.).

The Autorité calls on professional associations to exercise the utmost vigilance, in particular with regard to the information exchanged and the pricing and non-pricing guidelines (including on environmental parameters) likely to be circulated to members

Charging stations for apartment buildings

Popular with electric vehicle users, home charging is easily accessible in single-family homes, but much more complex for those living in apartment buildings.

The rate of co-owned properties equipped with EVCI remains very low, with only 2% reportedly having any charging facilities. Several factors may be at play, including the limited attractiveness of the individual solution, i.e. the right to a plug, and, for the shared solution, a financial barrier linked to the need for financing for the installation of the shared infrastructure within the building, a technical barrier linked to the configuration of the parking spaces to be equipped and a regulatory barrier linked to the decision-making process within collective housing and, more singularly, in co-owned properties.

Against the backdrop of the new European Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, adopted in April 2024, the Autorité makes a series of recommendations to facilitate and fluidify access to charging in apartment buildings for end users and to ensure the development of healthy competition in the sector.

The Autorité agrees with the observation of the CRE that “the installation of charging stations in the car parks of buildings used primarily for residential purposes can pose technical, organisational and competitive challenges”.

Technical specifications inherent in the deployment of charging stations in apartment buildings

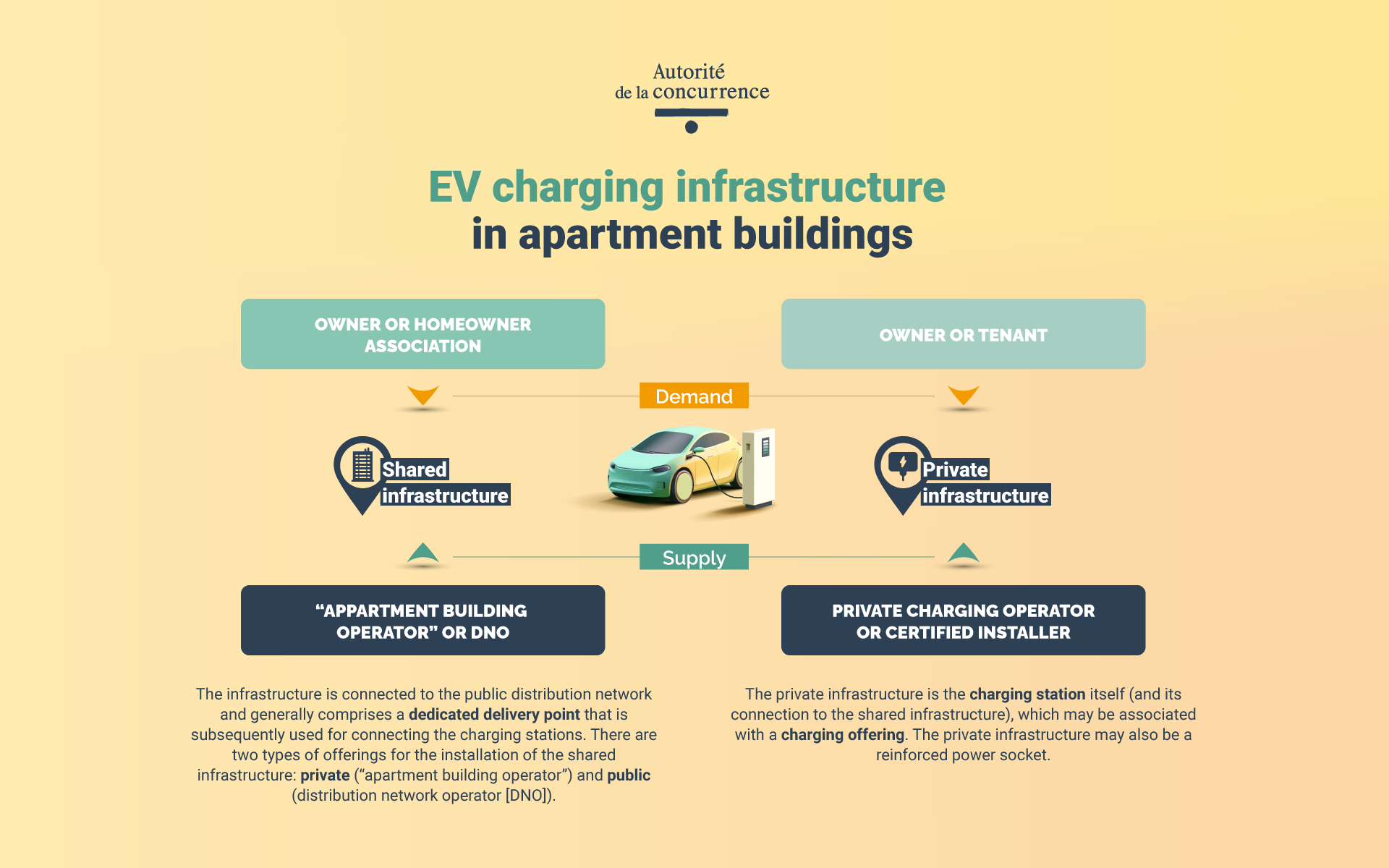

The deployment of charging stations in apartment buildings involves technical requirements. With the exception of the individual solution embodied by the right to a plug, equipping a building involves installing:

- shared infrastructure, connected to the public distribution network (“PDN”) which includes the shared electrical system, generally comprising a dedicated delivery point that is subsequently used for connecting to the charging stations;

- private infrastructure: the station itself and its connection to the shared infrastructure.

For shared infrastructure, apartment building operators (“ABOs”) and the distribution network operator (“DNO”) supply the EVCI, with demand from owners and homeowner associations.

For private infrastructure, private charging operators (“PCOs”) and certified installers supply the EVCI, with demand from owners/tenants.

The competitive situation in the sector

As in the case of publicly accessible EVCI, the Autorité found that the sector is dynamic and not yet mature, with players likely to enjoy competitive advantages due to their combined activities, which are a source of competitive risk.

The EVCI sector in apartment buildings has two major characteristics from a competitive point of view: first, the involvement of the DNO, which is also entrusted with a public service mission, in a competitive sector, and second, private offerings from ABOs which, in addition to installing the shared infrastructure, also offer an individual charging solution for each end user.

The Autorité points out that its role is not to recommend a connection plan, its sole aim being to preserve the competitive dynamic and free choice for consumers. Owners and homeowner associations must be able to select a connection plan and financing method objectively and transparently, based in particular on the reality of costs and the downstream impact on owners/tenants, which is not currently the case.

- Risks associated with DNO involvement in a competitive sector

In addition to its legal monopoly on connecting shared infrastructure to the PDN, the DNO also operates in a competitive sector, installing the shared infrastructure.

However, diversification of its activities gives rise to a series of competitive risks:

- possible asymmetry in connection times for shared infrastructure, depending on the solution – public or private – chosen by the owner or homeowner association;

- potential promotion by the DNO of its shared infrastructure solution, pre-financed by the tariffs for the use of the public transmission electricity grids (“TURPE”), at the same time as exercising its connection monopoly activity;

- possible cross-use of commercial and technical information by the DNO for the benefit of its parent company, and vice versa.

While the solution proposed by the DNO is likely to significantly limit the upstream attractiveness of ABOs’ shared infrastructure offerings, it has the advantage, in its current form, of preserving the freedom of consumers (owners/tenants) to choose their downstream charging offering (reinforced socket or station, with an electricity supply contract or a specific subscription).

However, in light of the above findings, and in line with the position of the CRE, the Autorité considers that it would be appropriate to reaffirm the priority allocation of the TURPE pre-financing mechanism to the installation of shared infrastructure in areas where private initiative has been identified as lacking, i.e. mainly car parks outside apartment buildings.

Refocusing the system would link the activities of the DNO to its public service mission and put an end to its involvement in a competitive sector.

If the system is not refocused, the Autorité recommends that the French government require the DNO, as part of the agreement signed with the owner or homeowner association, to increase the transparency of all shared and individual costs to be borne by the owner or homeowner association and end users, to make it easier for them to choose between the DNO solution and the private solution.

- Competitive risks associated with ABO/PCO offerings

The commercial and contractual strategy of ABOs/PCOs must, like the involvement of the DNO in a competitive sector, be the subject of particular vigilance.

In fact, the Autorité noted the existence of competitive risks likely to create artificial barriers to entry and expansion in the sector and to contractually lock in customers.

Risks associated with owners/tenants being captured by the ABO/PCO that installed the shared infrastructure at the time of signing the contract for the apartment building

The Autorité found that subscription to charging services could be conditional on the prior installation of the shared infrastructure by the same operator, suggesting the existence of coupled offers.

This situation arises in a context where vertical inter-compatibility between the shared infrastructure of operator X and the individual charging solution associated with the private infrastructure of operator Y is not mandatory.

However, this inter-compatibility is a sine qua non condition for preventing owners/tenants from becoming captive to the shared infrastructure operator, and, ultimately, for ensuring the competitive functioning of the sector.

After analysis, the obstacle to inter-compatibility appears to be contractual rather than technical, and seems to be the result of a contractually defined commercial strategy implemented by the ABOs.

- The Autorité calls on the legislator to impose an inter-compatibility obligation on the ABOs. Such obligation must be expressly set out in the agreement between the operator and the owner or homeowner association.

- Closely related to this recommendation, the Autorité invites ABOs/PCOs not to make the signing of a subscription contract by the end user conditional on the prior signature of the agreement on the shared infrastructure of the building (similarly, the termination of each contract must be independent).

Risks associated with owners/tenants being captured by the ABO/PCO that installed the shared infrastructure during or at the end of the contract

The Autorité considers that the owner or homeowner association should have the option of changing operator during or at the end of the contract, for example if the services of the current operator are no longer suitable, or if the services of another operator are more attractive.

- With this in mind, the Autorité recommends that ABOs ensure that owners and homeowner associations are fully informed of the exercise of any tacit renewal clauses, in accordance with Article L. 215-1 of the French Consumer Code (Code de la consommation), and limit the duration of renewals (at the very least, include in the agreement a reasonable notice period for termination during renewal periods), and contractually clarify continuity of management and maintenance in the event of a change of operator, both during and at the end of the contract.

- Lastly, the Autorité recommends that the French government should require, as a minimum for future agreements, that clauses relating to the transfer of ownership of the shared infrastructure and the terms and conditions on expiry of the agreement should systematically be included in shared infrastructure agreements.

Opinion 24-A-03 of 30 May 2024

Contact(s)